Sports

Lance Armstrong Rides On

Story by Abby Schreiber / Photography by Kristi + Scot Redman

07 June 2018

In the five years since he first admitted to Oprah — and the world — that he had used performance enhancing drugs, Lance Armstrong has been working hard to rebuild his life and regain the public's trust. In the wake of settling a lawsuit that had been hanging over his head for eight years, Armstrong reveals more about his past while remaining firmly focused on his present and energized for his future.

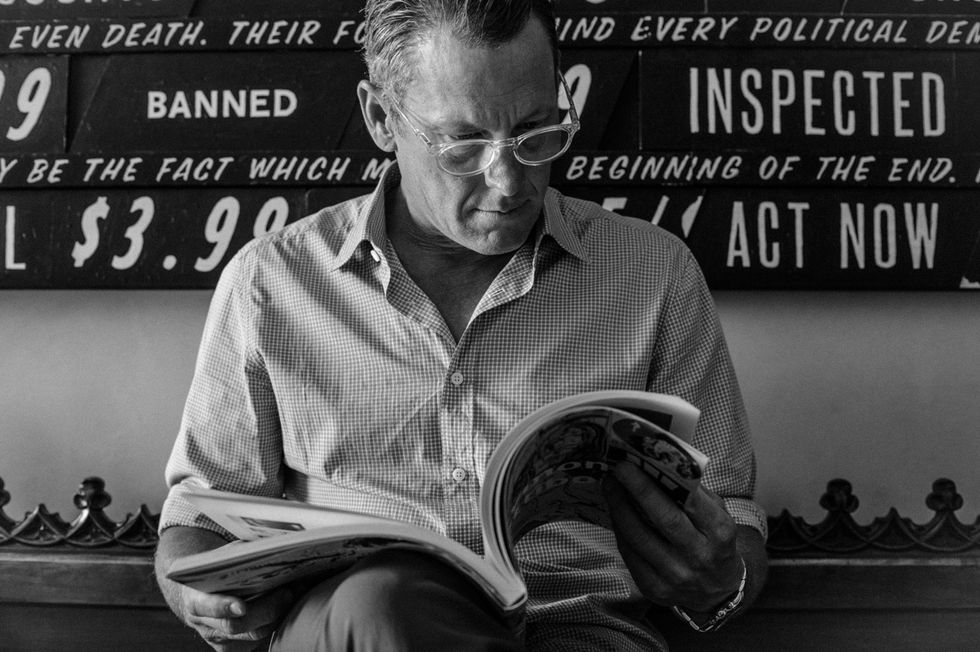

It's a piercingly sunny day in Austin, Texas as my Uber pulls up to Lance Armstrong's grand, Mediterranean-style mansion. Armstrong's manager, Mark, lets me inside and, walking through the front door, I find a crowd gathered in the living room, chatting amidst a large Kehinde Wiley painting and several other pieces of eye-catching contemporary art. The photographers are setting up their lights, the groomer is setting out her kit and Armstrong has just returned from a workout. Sweaty, he jokes, "We just finished!" pretending to have gotten his portrait taken in his gray T-shirt and gym shorts. While the team finishes prepping, he heads upstairs to shower and change, but not before asking if he should wear anything in particular. "Put on whatever you normally wear — whatever makes you feel most like yourself," I tell him. A few minutes later, Mark gets a text message from Lance upstairs. "Should he wear shoes?" Mark asks. "Yeah, let's at least have a pair on hand for full-length shots," I reply.

Pretty soon a freshly scrubbed Armstrong ambles downstairs — gray slip-on shoes on his feet — and gets in front of the photographers' camera, gamely following instructions to turn his head just so or train his gaze in a particular direction. He laughs and jokes throughout the photo session and, for the final shot, indulges us by putting on his new clear-framed reading glasses that he says he recently ordered for cheap off Amazon.

Related | Leo Messi: G.O.A.T.

In no time at all, the team agrees that we got the shot. The portrait session happens so easily and so seamlessly — with its subject so easy-going and so chill — that it's hard to square the man smiling and chatting with us with the same guy whose famously combative interactions with the press over a decade ago could provide an entire reel's worth of pursed lips, dagger stares and ice cold "I have never doped" lies. Today, he's practically a living, walking embodiment of the Taylor Swift "Look What You Made Me Do" meme: I'm sorry, the old Lance can't come to the phone right now.

His relaxed mood is no doubt buoyed by the recent news on April 19 that he and his lawyers had reached a settlement with the United States Postal Service and Floyd Landis, agreeing to pay $5 million to settle a case that had been hanging over his head for years. The case started after Armstrong's former teammate filed a whistle-blower lawsuit against him back in 2010, alleging that Armstrong had defrauded their team sponsors — the USPS — by doping during the Tour de France. Essentially, the suit claimed, Armstrong had broken his contract by taking sponsorship money from the government while cheating. The Department of Justice joined Landis' suit in 2013 and, in the process, Armstrong faced up to nearly $100 million in damages if he were to be found guilty. And so, despite the fact that $5 million isn't exactly chump change, the outcome, given the alternative, still felt like somewhat of a relief.

"The weight of what the potential downside was, was crazy," Armstrong says, in his first interview about the case since it reached the settlement. He continues, "Having said that, we were confident," adding, "In the back of my head, I didn't think we would go to trial. I figured we would settle." Nevertheless, he reveals here for the first time that he and his lawyers staged a mock trial in DC to prep for the possibility that they would have to go to court. But, according to Armstrong, the outcome pointed to a decision in his favor, and "it wasn't even close." The main challenge for the USPS was to prove that Armstrong's doping and lies caused material damages to the organization. Armstrong says, "It would've been very difficult for them to win the case based on the fact that the way these cases work, you actually have to prove the damage and you can't just say, 'Well, there were one billion negative articles.' That sounds terrible, but if you don't lose money or lose clients, then that doesn't matter. [The USPS] freely admitted that they could not show that."

In the Homeric saga that's been Armstrong's life for over twenty years (or, frankly, since he was born), a life full of very high highs and very low lows, there's something about this latest twist that feels notable, more definite. It's been a little more than five years since he first sat down with Oprah in January of 2013 and finally admitted to the world that yes, he had doped and yes, he had been doping during his seven magnificent Tour de France wins. That interview was not only an admission of his doping but also a puncturing of his storybook hero's journey of a kid from small-town Plano, Texas who became a rising star in the cycling world only to be diagnosed with testicular cancer at the heartbreakingly young age of 25 and given less than a 50% chance of surviving the disease, which had spread to his lungs, abdomen and brain, before he ultimately beat the odds, kicked cancer's ass and made a full recovery that not only restored his normal life but saw him win the Tour de France seven times, all the while starting a foundation that raised half a billion dollars to fight cancer and support survivors. And in that time since he's come clean, he's been slowly rebuilding his life while living under the cloud of this case. Now, it seems, he might finally be able to truly move on.

These days, moving on means focusing on WEDU, a brand he conceived in 2016 that encompasses content (two podcasts he hosts: an interview show called The Forward and a recap of cycling races like the Tour de France called Stages, soon to be re-branded as THEMOVE); endurance sport events (like The Hundred, a 100-mile bike ride outside Austin, TX); and merchandise. According to Armstrong, the brand's name serves to answer any question along the lines of, "Oh my god, who wants to go run the Boston Marathon in the snow and 35 degrees and 20-mph headwinds?" Or, "Who wants to run an Iron Man?" Or, "Who wants to swim across the English Channel?" In other words, Who'd ever want to do something so difficult and so strenuous? We do! The company allows Armstrong to maintain a connection to the cycling and endurance sports worlds and participate in events, something that he has otherwise limited access to do. As a consequence of the 2012 report by USADA (the United States Anti-Doping Agency) that preceded his Oprah interview and concluded he'd been doping, he was banned from competing in any sanctioned events for sports that are offered in the Olympics, and while part of this ban was lifted in 2016, he is still banned from competing in sanctioned cycling events for life.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of WEDU is Armstrong's wide-ranging podcast, "The Forward." Structured as hour-long interviews, the podcast features an eclectic group of guests whose only real connection is that they're people Armstrong finds interesting. He's talked porn with former adult film star Mia Khalifa, politics with Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel, campus sexual assault with author and journalist Vanessa Grigoriadis, Russian doping with Icarus director Bryan Fogel and many other varied topics with equally varied guests. In an ironic twist, a man who once sued journalists for daring to out him as a doper, is, in a way, entering the profession. His interviews are relaxed yet well-informed, and Armstrong says it's the entire day he spends doing his "homework" and "studying [his guests'] lives" in preparation for interviewing them that he finds most rewarding. "I was not a great student in school and homework was the last thing I ever wanted to do, so it's been wild to all of a sudden love that part," he says. "I love reading about people and trying to figure out their history and things they've overcome in their lives, and then trying to figure out what's the safe way to go about getting into that."

He says he's most proud of an episode he taped with Michael Morton as his guest, a Texas man who had been falsely accused and convicted of raping and murdering his wife in 1986. Morton went to prison for nearly 25 years, during which time he found God and refused to lie and plead guilty when the opportunity came up for him to be paroled. "He was about to get paroled, but the deal with parole is you have to admit guilt and show contrition and remorse, and Morton said, 'I didn't do it, and I'm a man of the Lord, and I'm not going to lie and I'm not going to lie to get out of here. So I'll stay,'" Armstrong says. In the interview, Armstrong asks Morton about his faith and forgiveness, and whether he forgives the man, eventually apprehended, who did rape and murder his wife. Morton replies, "No."

Although his critics have long accused Armstrong of having a huge ego or suffering from narcissism, this keen interest in the lives of others has been present for a long time. Both during his days as founder and chairman of the Lance Armstrong Foundation (now known as Livestrong) and in the years since the organization cut ties with him back in 2012, Armstrong has devoted a significant part of his life to meeting and communicating with those who are fighting, or who have survived, cancer. Over the years he's made countless visits to cancer wards to meet and speak with patients, and he still regularly records video messages to patients and survivors, giving them words of encouragement and, occasionally, advice. In this post-Livestrong era, Armstrong and his fiancée Anna have become involved with Camp Wapiyapi, a Colorado summer camp for children diagnosed with cancer and their siblings. The couple hosts a bike ride, dinner and auction each summer that raises money for the camp.

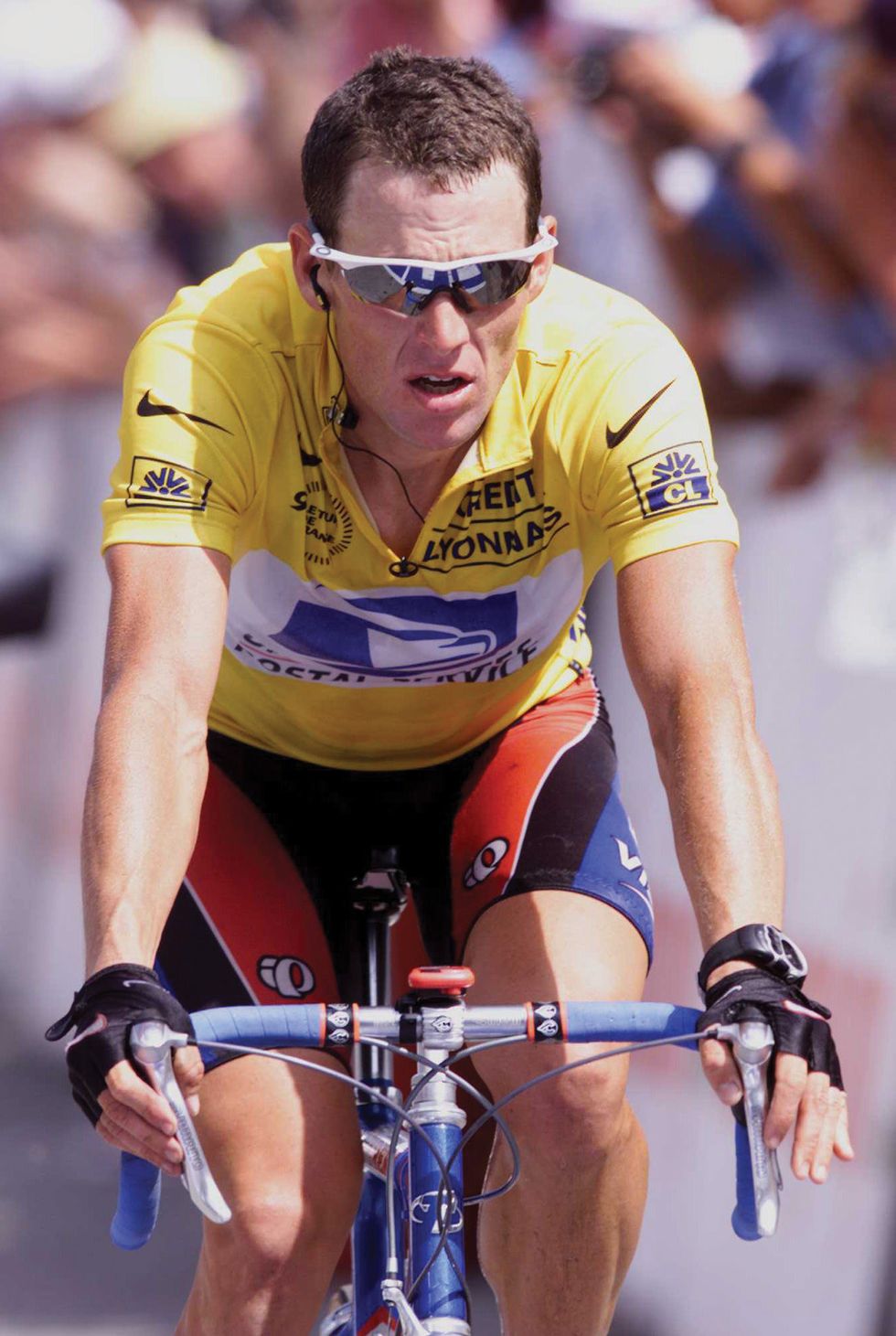

Photo by Tom Able Green / ALLSPORT via Getty Images

Just as his involvement with Wapiyapi and his personal outreach to cancer survivors has allowed Armstrong to maintain a connection to something very meaningful to him in the face of changed circumstances, so too has his podcast Stages allowed him to dip his toe back into the world of the Tour de France, albeit as an outsider watching on TV rather than as a cyclist competing in the race. Talking about the experience of watching young riders compete in a race he once dominated but which now has practically tried to erase him from it, having stricken all of his wins from the books due to his doping, I ask if he thinks the Tour has finally gotten itself clean. "I have no idea," he says of whether the cyclists are continuing to dope. "I'm so alienated and removed." Still, he's puzzled by the fact that although riders' "times are faster" today than back when he and his teammates were competing, "the performances are not nearly so dynamic" and there aren't as many thrilling breakaways like the moves Armstrong once made famous. But he stops short of conclusively weighing in one way or the other as to whether anyone is using performance-enhancing drugs.

By now it's common knowledge that Armstrong was part of the "dirty generation," a time when doping was basically ubiquitous throughout cycling and at the Tour de France. (In 2013 the New York Times published a graphic showing that of the top 10 finishers in the Tour de France from 1998 to 2012, more than a third had "either tested positive, admitted to doping or been sanctioned by an official cycling or anti-doping agency.") His big post-cancer comeback in 1999 came a year after the Festina Affair, a scandal that rocked the cycling world after a soigneur (a cycling world staff position that's almost like a hybrid masseuse and tour manager) for the namesake team was caught by police officials at the France-Belgium border trying to smuggle performance enhancing drugs. His haul included EPO, or erythropoietin, which boosts the production of red blood cells. EPO was a hot drug at the time (partly because there were no tests to detect its presence back then), and one that Armstrong and many of his teammates would later end up admitting having taken.

From the jump, Armstrong's return to the cycling scene in 1999, a year that saw his first Tour de France win, was dogged with doping allegations, partly fueled by his association with an Italian doctor named Michele Ferrari who already had a reputation for being involved with performance-enhancing drugs by the time Armstrong started working with him. Ferrari put Armstrong and his teammates on a regimen that included EPO as well as cortisone and occasionally testosterone. Later they'd start "doping" with their own blood via transfusions. They'd withdraw oxygenated blood when they were at rest, then put it back into their bodies after their cells had been depleted of oxygen during competition. As you can imagine, the logistics of carting around bags of blood — and keeping them cool — were complicated.

Armstrong explains here for the first time a few more details about how they pulled it off.

"In Europe, things like milk, juice and chicken broth come in those Tetra Pak boxes, and there's a little pop top," he says. "Those boxes are the same size as a blood bag." The team would enlist friends and associates to stockpile these boxes and "slice up [the bottom]" while "the top was maintained and the seal was the same." He says they'd "cut the boxes open, dump the milk or whatever was in there out, clean it, drop the blood bag in and then glue it together." They'd rent these associates an RV to pose as tourists following around the Tour, and they'd drive these blood bag-containing-boxes around before dropping them off with the team van or team hotel rooms later on. "It sounds sneaky or smart, but, I mean, it's pretty primitive," Armstrong says.

Though doping was and is the main way we think of cheating when it comes to cycling, the sport has long been known for creative (and even downright odd) ways of gaming the system since its very beginnings. While riders of yore boosted their performance with everything from beer to cocaine to amphetamines, they also did things like hop in trains or cars when they just couldn't pedal any longer, or they would bite down on a cork that had string or wire attached to it whose other side was attached to a car that'd pull them along. While the cork maneuver may no longer be in vogue, Armstrong says it's still common — even today — for riders at the very back of the pack to occasionally hitch rides with cars far out of view of the crowds and cameras that are chasing the front.

Photo by Lars Ronbog / FrontzoneSport via Getty Images

And then there's the sneaky practice of "sticky bottles," or when riders get water bottles handed to them by team directors following along in a car. When the riders grab the bottle out of the driver's hands, the driver "guns the car," giving the rider a momentary boost. Armstrong alleges this is, in part, what gave his former teammate Floyd Landis his 2006 Tour de France win (which he would later get stripped of for doping). That year, Landis had won one of the race's stages — and got to wear the coveted yellow jersey — but then the next day "lost, like, seven minutes," Armstrong says. "Everybody was like, 'Ok, the race is over'" but then a day later he miraculously regained his lost time. "If you watch [Tour footage], somebody counted it and he took 250 [sticky] bottles," Armstrong claims.

Given the frequency of cheating, it can feel like the ways professional cycling in general, and the Tour de France in particular, are structured create perverse incentives for athletes to break the rules. Not only is a three-week race like the Tour de France grueling enough but that's also on top of the fact that many professional cyclists are competing in the race in the midst of a punishing calendar that includes many other events, some of which are also three weeks long. "The question comes up, 'Should the Tour de France be two weeks instead of three weeks?'" Armstrong says. "I've always advocated for keeping the Tour de France at three weeks but all the other races — like the Tour de Italy and the Tour de Spain, which are three [weeks] — should be two [weeks]." Or, he proposes, all three Tours could decide to become two weeks long. "Right now nobody could win all three races at three weeks long. Impossible. I don't care what meds they give you. But if they were all two weeks, one man could win them all. The grand slam. Which is a pretty fucking dope idea, if you think about it." But he acknowledges this is all wishful thinking. "The problem is the Tour [de France] won't [do this]. That's a week of their lives, a week of business, a week of revenue. It cuts their business by a third. And they rule the sport." He adds, "It ain't gonna happen. But it's a good idea."

Much as money and politics can seep into Tour logistics, cycling can also be very political, and sometimes whether a rider wins or not has less to do with his skill or luck on race day than it does the behind-the-scenes jockeying and horse trading teams engage in. "It's not allowed for money to exchange hands," Armstrong says, but, beyond that, informal race fixing does pop up. Even so, there have also been cases of teams paying off others to fix a race. Back in 1993, Armstrong, still a first-year pro, was poised to win the Thrift Drug Triple Crown and take home a million-dollar prize if he won all three races in the circuit. He's alleged to have been part of a plot to pay off competing riders $100,000 so they'd let Armstrong win the third and final race, the CoreStates USPRO Championships in Philadelphia. "That did happen," he admits. But, he says, although he was the beneficiary, he wasn't the mastermind. Instead, he alleges that the team manager, Jim Ochowicz, was the one who had arranged it, a claim denied by Ochowicz himself.

Hearing these revelations old and new from Armstrong about all of the ways he, his teammates and his competitors had cheated over the years impresses upon you the level of risk and recklessness they were all undertaking. Though it was widespread throughout the sport, as a leader and a champion, Armstrong perhaps risked losing the most if he got caught (and so, in fact, he did). When discussing his appetite for risk, the conversation turns to what role, if any, his having survived cancer played in all of this. When you're staring death in the face and overcome it, might any other risk or challenge feel minimal and inconsequential by comparison? "I think there's probably science to support that," Armstrong says, acknowledging the possibility.

But the fact is, for all of the risk he took over the years with doping, you could argue that it wasn't the drugs that led to his downfall but the way he treated other people. Many people — and even Armstrong himself — have pointed to his lies, betrayal and bullying of teammates, teammates' spouses, team staff and journalists as being crimes bigger than his using drugs, and it's clear all of these things contributed to his having gotten investigated by USADA and ultimately losing so much.

The chain of events that ultimately led him to that 2013 admission on Oprah began back in 2008 when Armstrong decided to make a comeback, having retired from competition after his seventh Tour de France win in 2005, and enter the Tour in 2009. Early on, he remembers having a sense of foreboding that he might be making a colossal mistake. He remembers when the former director of the Tour, Jean-Marie Leblanc, wrote a letter in Le Figaro in response to Armstrong's intention to compete once more in the Tour. In his letter, Leblanc urged him not to do it. "Me in 2008 reads that and I'm like, 'Shut the fuck up. I'll do whatever the fuck I want to do,'" he recalls. But, after reading what LeBlanc wrote — words to the effect of "We associate you with the past, with that past generation that we know was not a perfect generation" — Armstrong suddenly realized, "Fuck. He's right. I can't do this. I should not do this."

He recalls feeling "every fiber in my body say, 'Don't do this.'" But, he says, by that point, "The wheels were already in motion. The Nike machine was in motion, the Livestrong machine was in motion, the Trek machine was in motion. It would've just taken one phone call — I could've just said, 'I hurt my knee.' I could've said, 'I have depression.' I could've said anything! It would've been two days of mixed press and that would've been it." But Armstrong didn't say anything and went on to compete in the 2009 and 2010 Tours. He's adamant that, despite accusations from critics to the contrary, he rode both races completely clean — and that includes not having done blood transfusions. He came in 3rd place and 23rd place, respectively.

By this point, his former teammate Floyd Landis had been accused of doping during his 2006 Tour de France win and stripped of his championship in 2007. After initially vigorously defending himself of the charges, he came clean on April 30, 2010 in an email to the then-CEO of USA Cycling, Steve Johnson. In his email, Landis revealed that his former USPS teammates were involved in a teamwide doping effort, outing Armstrong in the process. The two cyclists had seen their relationship hit a low point after Landis was denied a spot on Armstrong's RadioShack team to compete in the 2010 Tour of California. So, whether out of a desire to blow the whistle or out of revenge (or both), Landis sent that fateful email whose repercussions would alter his, Lance Armstrong's and cycling's reputations forever.

USADA opened an investigation shortly thereafter, which led to those damning findings in 2012, and Landis filed his suit that same year. Along the way, a federal investigation was launched by then-Food and Drug Administration special agent Jeff Novitzky (who had previously investigated Barry Bonds and Marion Jones for steroids) that same year but was later dropped in 2012. The DOJ joined Landis' lawsuit in 2013, which brings us to the present day and its eventual settlement.

Armstrong can't go back in the past and change his doping behavior, but he knows he can change that other root issue — his treatment of others. In previous interviews he's mentioned having apologized to people he's hurt, people like the former USPS soigneur, Emma O'Reilly, who revealed Armstrong's doping in a 2003 interview with an Irish journalist named David Walsh and went on to face Armstrong's wrath (and his aspersions about her alleged drinking habits and romantic activities). O'Reilly has said she forgives Armstrong, and he even wrote the foreword to her book.

Two people he may have a harder time reconciling with, however, are his former teammate Frankie Andreu and Andreu's wife Betsy, the latter of whom has been one of his most visible antagonists over the years. Armstrong revealed on Oprah that he'd called the Andreus to apologize around the time of that interview, but things seem to be on shakier ground today, after transcripts leaked of a deposition Armstrong gave for a USPS case pre-trial in which he claimed Frankie Andreu had doped throughout the majority of his career, something Frankie has denied. (Andreu has said the time he spent doping was a much more minimal part of his career.) And, for Armstrong's part, it seems that despite all of the time and all of the apparent emotional growth, a mention of Betsy still strikes a nerve. While Armstrong speaks freely and answers every question with candor throughout our interview, a query about Betsy's infamous accusation that she witnessed Armstrong reveal to his cancer doctors in an Indiana hospital room back in 1996 that he had previously used performance-enhancing drugs was met with a tense denial. Echoing earlier interviews (the question has dogged him in many major interviews from Oprah to the BBC), he says, "Does it make you feel better or the whole world feel better if I just — you want me to lie and say, 'Okay, yeah!' Then I'll say that! But we're way past talking about that." He continues, "If I don't remember that happening, then I mean — first of all, technically it couldn't have happened. A doctor does not walk in a room with 20 other people and talk about seriously sensitive medical data information and history in front of strangers. They don't do it. Just on the surface. And no matter how much somebody might say, 'Well, the patient just said, "Tell them, I don't care"' — absolutely not."

But Armstrong's complicated history with the Andreus aside, it's nevertheless undeniable that the intervening years have made a big impact on him and that he's been working hard to chip away at his old defensive instincts, anger and aggression. He says he's also been attending therapy for years now, since even before he got caught doping (despite previous media reports to the contrary). One of the toughest topics he says he's tackled with his therapist is the idea that his actions caused others to become complicit in his lies. It's something he learned about in real life, after recently reconnecting with a former Livestrong employee who told him of having been instructed to parrot his lies and talking points like he "never failed a drug test" in his defense. "It fucking floored me," Armstrong says of hearing that, adding, "and the reality is there are millions of those people" who felt the same way.

He says he also attends group therapy sessions with his family, and that talking with his kids about his past has been a difficult road to navigate and "is not a one-time thing." He adds, "My deal is [my kids and I] can have this conversation a hundred times. So if they have other questions or other things they want to talk about, I'll never say, 'Look, we've already talked about that and we're done.' It's a commitment for as long as they want to have that dialogue about my past. I think that makes them feel better about it."

What's also particularly challenging about his situation is the fact that although his three oldest kids with his first wife, Kristin, 18-year-old son Luke and 16-year-old twins Grace and Isabelle, were old enough to be aware of what was happening when Armstrong came clean back in 2013 and have talked to him about what happened in the years since, his two youngest children with his fiancée Anna, 8-year-old Max and 7-year-old Olivia, are just starting to learn about everything. In a previous interview with Outside magazine, Anna describes talking to their son Max about Armstrong's career and explaining to him that his father was one of the world's top cyclists only to have Max respond, "Yeah. But he cheated."

But one silver lining in the midst of all that's happened in the past five years is that he's gotten to spend a lot more time with his family. It's clear he dotes on his five kids, and his Instagram is filled with pictures of them, like Armstrong and his daughter Grace going on a father-daughter bike ride ("Thanks @grace.armstrongg for inviting me to ride with you this morning!! Love ya G! @isabelle.armstrong, when we getting you on the bike?!") or the family celebrating his son Luke's recent decision to commit to the Rice University football team ("Woot woot! Hey @riceuniversity, here comes your next student/athlete @luke_armstrong65! So incredibly proud of my son and the young man he's become. He's a great friend, teammate, and brother to his 4 siblings. I canNOT wait for the next chapter. Love you Luke!! #riceowls #ricefootball").

When not spending time with his family, taping podcast episodes or doing other work for WEDU, Armstrong finds time to indulge two other passions: golf and collecting art. He's particularly excited to talk about this latter interest and is happy to give me a little tour of some of his pieces in his Austin home on the day of my visit. He points out a big map of Texas by Tom Sachs, a large Rob Pruitt piece from his Gradient Faces series and a big painting by Os Gemeos. He says he first got into art in the late '90s shortly after he bought his first house. He learned more about art and artists while he lived in Europe, and in the 2000s, his interest became more serious as he started really collecting pieces and attending art fairs. He says he likes going to Art Basel and the Armory Show and always makes a point to check out all of the satellite fairs. "I just walk around and I don't shop for names. I just look and if something strikes, so long as it's not a gazillion dollars, I'm just like, 'I gotta have it. I love that.'" He says he's a big collector of work by Ed Ruscha, who he also considers a close friend, and also likes Dustin Yellin, Raymond Pettibon and Mark Ryden, along with the artists whose works he pointed out to me earlier. "I like stuff that's a little edgier," Armstrong says. "It's fun being a liberal in conservative Texas. You walk into my house and there's [a wooden sculpture] by Morgan Herrin of a naked lady or there's skate decks on my desk of someone flipping somebody the bird. Shit like that. I like that these Trump voters walk in and are like, 'Oh my god. Whoa, this guy's weird.'"

He acknowledges that as far as the wildly expensive art market goes, he's "been out of the game a bit just because it's been a little tight cash flow-wise" but that he "plans on jumping back in." On this rather delicate topic, there's a lot to ponder. While he's famously said to have once estimated his wealth as "$100 milski" before the doping scandal, he's said to have lost $75 million in sponsorship endorsements after the USADA case wrapped up in 2012 and has paid what's estimated to be about $36 million in legal fees as a result of all of the lawsuits and legal fees thereafter. And yet, even if he no longer has a private jet and can no longer drop insane amounts of money on art, it's clear that he's still very, very well off. But it's reasonable to wonder whether his wealth is all from savings or someplace else.

"One other area that people don't know about is investing. I'm a super active investor and have had some incredible luck. Without that we'd be bust," he texts me in a follow-up exchange a day after our chat in his house.

When I ask him if he'd be comfortable sharing some of the investments he's made on the record, he cryptically texts:

"How did you get from the airport to your apartment???"

Turns out, Armstrong was an early-stage Uber investor.

"Very very early. Company was valued at 3.7 mil. Mil not bil," he types.

"I got into Uber via chris Sacca (lowercase capital) who is a bud of mine. [G]ave him a 100k. Mind boggling what it's worth now"

So, needless to say, despite all of the turmoil he's had to deal with over the last several years (much of it self-inflicted, he'll readily admit), it seems more apparent than ever that he's finally emerging on the other side. "I was talking with somebody in a restaurant and I said, 'I'm the most powerful person in this room,'" Armstrong recalls. "When people think of power, they think of wealth and prestige and class and position and job title, and that's not what I mean. When I say power, I mean I know exactly who I am and I know exactly who my friends are. I know what my community is. You can't learn those things, you can't teach those things, you have to go through Armageddon like I did. I don't recommend it for many people, but it's a super-powerful place to be in life." He adds, "And it's fun, too."

Photography: Kristi + Scot Redman

Grooming: Mel Martell